Yellow Fever and the Strategy of the Mexican-American War

David W. Tschanz, MSPH, PhD

March 26, 1847 found Major General Winfield Scott in a strangely anxious mood. His army had successfully landed, then invested, the Mexican city of Veracruz. His decision to lay siege to the city -- the most heavily fortified in the Western Hemisphere -- rather than storm it was criticized by some, but the constant American bombardment was starting to have the intended effect. Morale inside the Mexican city was collapsing and it was clearly only a matter of time before the city capitulated.

The cause of Scott's anxiety, in fact, had little to do with the actual military situation. His eye was on the calendar and the steady march of days. Already two months off his original timetable because of incompetence in the War Department, Scott's nerves were on edge because of reports from his medical officers of disease in the ranks. It was this same disease that had dictated the entire strategy and original timing of his assault and now it looked as if every delay would bring it into contact with his forces.

The Mexican called it La Vomito. A fifth of those who developed it were doomed to die. Victims were racked with headache, fever, chills and vomiting. Their skin took on a pronounced yellow color as their liver was damaged then failed. Splotches of blue and black appeared on the skin as blood vessels ruptured and hemorrhaged into the surrounding tissue. Inside the body the same process cut off the blood supply to major organs. Blood seeping from damaged arteries and veins filled the lungs and the victim began to drown in his own fluids. In the severely stricken the vomit took on the consistency and color of coffee grounds–in reality coagulated blood–as the afflicted literally began to vomit up his own life blood.

La Vomito frightened Scott more than the Mexicans. Santa Ana's force he knew he could defeat. But La Vomito–yellow fever–was an opponent he was helpless against. Nineteenth Century physicians knew neither its cause nor how it was transmitted. All they could do was provide clinical support for the victim's symptoms and hope for the best. Scott's only workable strategy was to avoid the disease. But it was getting too close to theLa Vomito season to suit the American commander.

Yellow fever, popularly called "Yellow Jack" because it was a common cause for quarantining ships and ships in quarantine fly a yellow flag or jack, was and is one the world's most dreaded epidemic diseases.

YELLOW FEVER IN THE NEW WORLD

A viral illness, yellow fever is transmitted to man by the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Yellow fever was imported to the New World as a result of the African slave trade, ironically necessitated by the importation of European diseases to the New World and the die off of about 80% of the native American population in the space of two generations. Aedes aegypti appears to have arrived at the same time, traveling from Africa as stowaways in the water casks on the same ships as the slaves. Shipboard outbreaks could wipe out entire crews.

Between 1693 and 1901, 95 separate epidemics ravaged the United States inflicting 500,000 persons and killing 100,000. Philadelphia was struck eleven times, one outbreak in 1793 killed 10% of the city's population. Boston and New York were ravaged seven times each. The disease occurred and recurred regularly in Charleston, Mobile, Norfolk, Baltimore, New Orleans and other cities along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

Yellow fever played a number of roles in New World history. Its presence effectively closed the Amazon Basin to European exploration and colonization. In 1801 Napoleon sent a French army, under his son-in-law General Leclerc, to suppress the Haitian rebellion of Toussaint l'Ouverture. No sooner had it landed then it was attacked by yellow fever. Of an army of 25,000 only 3,000 survived to return to France. Napoleon lost interest in a New World Empire. He called in the American commissioners James Monroe and Robert Livingston, who had been seeking to purchase New Orleans, and offered them the entire Louisiana Territory for little more than they had been prepared to pay for one city.

Together with malaria, yellow fever defeated the attempts of Ferdinand de Lesseps to build a canal across the Isthmus of Panama. De Lesseps, fresh from his canal building success at Suez, designed a canal across 120 kilometers of swamp and mountains. In 1884 he brought in 500 young French engineers to supervise construction of the new canal, which he thought would take three years. None of them would live to draw their first month's pay. In September the entire crew of a visiting British warship died of the disease. After losing one third of the entire European work force of 20,000, de Lesseps abandoned the project. The construction rights were sold to the United States. Benefiting from the new understanding of the role of mosquitoes in the transmission of the disease and the work of Walter Reed and William Gorgas, the Panama Canal was completed in 1904. Even then it was a close thing. An outbreak of La Vomito in 1904 caused coffins to be accumulated on the railway stations faster than they could be removed. Panic seized the workers and only a heroic anti-mosquito campaign saved the project from failure.

LA VOMITO AND THE PLANNING OF THE VERACRUZ CAMPAIGN

The Mexican-American war had gone extremely well as 1846 began to draw to a close. Major General Zachary Taylor's successes in the northern Mexico territories and the conquest of California were causes for national jubilation. However, the goal of a Mexican surrender had not yet been achieved and the need to "conquer a peace" was growing acute. President James Knox Polk and his military advisors decided that in order to force a Mexican capitulation, further offensives would be necessary. Mexico City was the obvious target. As well as being the political, financial and military capital of the country there was another reason to take it. Mexico City stood on the site of the ancient Aztec capital, Tenochitlan, and was of great symbolic value to the nation as a whole. Capturing it would convince the Mexicans of their complete defeat.

The immediate problem for the Americans was how to get there. An approach by Taylor's forces from the north was ruled out since he would have to cross the northern Mexico deserts. Instead Polk decided on a landing at Veracruz. Once this great city, the most heavily defended in the Western Hemisphere had fallen, the American army, following the same path as Cortes had, would march on the Mexican capital and end the war.

After much soul-searching Polk gave command of the American invasion force to Winfield Scott, the Army's senior general and a man he did not like. Scott was a Whig, whereas Polk was a Democrat. The invasion, if successful, would enhance the Presidential prospects of whoever commanded it. Taylor, whose successes in the north had him being touted as a Presidential prospect (despite the fact that he had never voted), was a reminder of this danger. Always the consummate politician Polk was not enamored with the idea of a Democratic war leading to the election of a Whig general.

Scott was also prone to arrogance and tactlessness. Earlier in the war he had written the Secretary of War that he was not interested in conducting a military campaign with the fire of the Mexicans in front of him, and political intrigue and opposition from the Democrats in his rear. Still, he was a superb military leader.

Scott was a stickler for detail, a brilliant planner, an expert logistician and one of the United States' most overlooked strategists and military commanders. His meticulously laid out plans for the assault, which he did not think he would be allowed to lead, were the reason Polk finally appointed him to command. Scott's entire plan was based on striking Veracruz during the winter, and marching west of the "Yellow Fever Line" into the Sierra Madres before the La Vomito season started. The memory of the fate of Leclerc's army was a vivid reminder of the power of yellow fever. Scott had no desire to see it repeat its victory this time on the American Army. Also driving him was the knowledge that in May he would lose a third of his forces as the enlistment period of the first volunteers came to an end.

Scott's plan, supported by Commodore David Conner, the naval commander, called for an invasion before the end of January. Conner wanted to avoid the terrible "Northers", storms which annually wreaked havoc with the Gulf weather and might threaten the invasion force with sinking. These same Northers also cleansed the swamps of mosquitoes and eliminated yellow fever in the area for a few weeks. By April however the winds would disappear and spring rains would bring forth a new generation of the disease-bearing insects. These biological interactions were unknown to Scott. All he knew was that taking Veracruz would not be easy and that he wanted to be in the high country of the Sierra Madres by the spring, before La Vomito could whittle his army away. The best time to attack, Conner and Scott agreed, was in late January. However both Conner and Scott failed to anticipate the ineptitude of the War Department.

It is doubtful that the War Department could have served the American cause any worse if they had been in the pay of the Mexican government and trying to foul things up deliberately. In comic opera fashion the War Department sent ships to the wrong ports, assigned troops to the wrong locations and failed to deliver equipment where it was needed. Elements of the army and navy arrived at the designated assembly point, the Island of Lobos, (about 120 kilometers east of Tampico), in dribs and drabs. It was maddening to Scott, whose attention to detail had earned him the nickname "Old Fuss and Feathers", as the entire month of February vanished amid the confusion. As if to remind him of what disease could do, an outbreak of smallpox caused the entire 2nd Pennsylvania Regiment to be quarantined on Lobos.

THE FIRST AMPHIBIOUS INVASION IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Finally, On March 9, nearly two months behind schedule, Scott launched the first amphibious invasion in American history. It was a rousing success. In less than 5 hours 10,000 men had landed without a single casualty. Scott and his men besieged Veracruz and maneuvered to invest it, while the navy blockaded and bombarded the city. Siege life was miserable for both the besiegers and the besieged. Mexican skirmishers kept the American sentries wary and trigger happy. Sand was everywhere and in everything. Happily living in the sand were sand fleas–all of them hungry and looking at the arrival of the Americans as an opportunity to gorge. Battling them took on almost the same importance as fighting the Mexicans–with some unusual results. Young Lieutenant Robert E. Lee and a colleague hit on the idea of covering themselves with pork grease to keep the pesky critters from feasting on them. This experiment in pest control had no impact on the sand fleas, but probably cost Lee most of his friends. Others dealt with the fleas by enclosing themselves completely in their canvas sleeping bags, usually resulting in the complete encasement of victim and a large number of fleas.

More ominously, cases of La Vomito began to occur in small numbers almost as soon as the forces landed, though not at epidemic strength. Scott knew that it was only a matter of time before it did and that it would cripple his army.

Inside Veracruz the citizenry was subjected to a demoralizing bombardment from the warships gathered in the harbor. Further lowering of civilian morale followed the American investiture of the city. Depressing the citizenry more, no relief appeared from Mexico City.

Mexican support from outside the beleaguered city was pitiful. Troops from the upland states of the Mexican republic refused to venture into the coastal regions for fear of the La Vomito, whose season was rapidly approaching.

As the bombardment continued Scott prepared to take the city by storm. He could not afford to be in the low country when the yellow fever season hit–around April 15th–and although he estimated US losses would be close to 2000 if such an assault was conducted, he recognized the eventuality of having to do the same rather than wait.

On March 25, a brief cease-fire was sought by the Mexicans. The foreign consuls inside the city asked that they be allowed to evacuate the civilians. Scott rejected the request. Dismayed the Mexicans realized that the constant bombardment would only continue. Chaos was already rife inside the city and the morale of the citizenry nonexistent. A late Norther struck that night and broke the back of what resistance remained. On the 27th, after a day of negotiations, the city and the fortress of Ulua surrendered to Scott.

On March 29 the Mexican garrison marched from the city, stacked their weapons in the rail yard and marched westward. By noon Scott was in possession of Veracruz.

Scott could not afford to dally in the city and began to advance along the National Highway toward Mexico City on April 2nd. At Cerro Gordo, a motley collection of Mexican troops, the so-called "Army of the East", attempted to halt the American advance. On April 18, Scott's forces won a crushing victory against the Mexicans.

Scott continued to advance along the highway higher into the mountains passing the city of Jalapa and the fortress of Perote. But now he could breathe a sigh of relief as he crossed the Sierra Madres range. He had passed the Yellow Fever Line and only one enemy remained.

Without enough men to hold the National Highway from his base at Puebla to Veracruz, Scott abandoned his line of communications entirely. "Scott is lost," said the Duke of Wellington in London, "He cannot capture [Mexico] city and he cannot fall back upon his base." Scott met Santa Anna's forces at Contreras on August 19th and at Churbusco on August 20th, defeating them on both occasions. On September 13, 1847 the American forces stormed the "Halls of Montezuma" and the city fell. The war was, for all intents and purposes, over.

THE COSTS

While the American Army did not suffer a major debilitating yellow fever epidemic, disease exacted a terrible toll. In addition to La Vomito, diarrhea, dysentery and typhoid claimed lives amid the poor sanitation of the camps. Other diseases such as measles, smallpox, mumps, syphilis, gonorrhea and cholera claimed lives in lesser numbers.

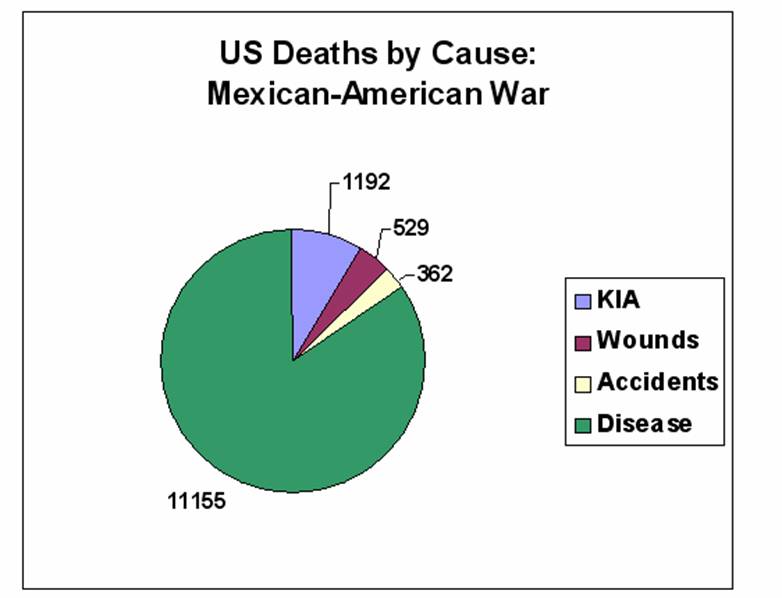

In totaling all deaths among American soldiers in the Mexican-American War 1,192 were killed in action, 529 died of wounds received in battle, 362 suffered accidental death and 11,155 soldiers died from disease. Disease claimed a toll seven times greater than that of Mexican weapons. Small wonder then that in preparing his campaign, Scott had sought to avoid adding to the count of victims for his unseen enemies.