The Man Who Saved Millions

By Sepp Jannotta, MSU News Service

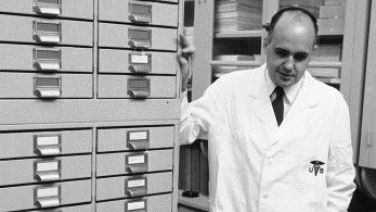

As he worked in a field at his family's farm one day in 1938, a teenage Maurice Hilleman was thinking about his future.

On the one hand, the recent high school graduate had been given a coveted career-track job at the local J.C. Penney just across the Tongue River in Miles City.

On the other hand, given his passion for science, not to mention a devotion to classical music, his brother had been urging him to leave Miles City and go to college. When Maurice had balked at the notion on grounds that he couldn't afford it, his brother informed him that there was scholarship money available for students to attend Montana State College in Bozeman.

As Lorraine Hilleman tells it, her late husband always thought of that moment as a pivotal point in his life.

"Standing out in that field, he made up his mind to attend Montana State College," she said. "He always said it was one of the best things that ever happened to him."

Mark Jutila, head of MSU's Department of Microbiology, said there's reason for the Montana State University community to feel the same way about Hilleman's decision that fateful day, because Hilleman helped establish MSU's reputation as a producer of world-class scientists.

"Given all the vaccines he was responsible for developing, Maurice Hilleman had an amazing impact on human medicine," Jutila said. "It's hard to imagine the number of lives he had an impact on, and for MSU that's a huge thing."

Even today, following his death from cancer in 2005 at the age of 85, the number of lives saved by the science of Maurice Hilleman is in the untold millions and continues to mount, according to Paul Offit, chief of infectious diseases at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Offit wrote Vaccinated: One Man's Quest to Defeat the World's Deadliest Diseases, a biography about Hilleman and his extraordinary career as a biomedical researcher.

Despite having developed eight of the vaccines routinely given to prevent an array of diseases and being arguably the most world-changing graduate in MSU's history, little is remembered about Hilleman's time in Bozeman. More often than not, within Montana the mention of Hilleman's name will draw a blank look.

Not so for Menga Huffman, who also grew up in Miles City and came to Bozeman in 1938 as part of the freshman class that included her friend Maurice Hilleman.

"He was clearly one of the brightest of people," she said.

An incredible work ethic and dedication to the study of science were evident from the start at Montana State, said Huffman, who still lives in Bozeman.

"Even in high school, he was totally dedicated to science," Huffman said. "And as a freshman, most Saturdays, when all the other boys were out at the football game, Maurice could be found working in the chemistry lab."

Hilleman graduated first in his class in 1941, having double majored in chemistry and microbiology. Acceptances for graduate study rolled in from the nation's top universities. Hilleman chose the University of Chicago because it was a center of ground-breaking science, though he confided to Offit that Chicago also held a special place to Montanans as the great American city at the other side of the wind-swept prairie.

In Chicago, Hilleman began to show his remarkable grasp of infectious diseases. His Ph.D. work reclassified chlamydia as a bacterial infection, a discovery that brought new and effective treatments for the sexually transmitted disease that caused sterility in thousands of women each year. It was the first step in a career marked by achievements that helped to nearly eradicate many once-deadly afflictions from the developed world.

The following are Hilleman's vaccine achievements:

- A hepatitis B vaccine that was the first vaccine to prevent a cancer in humans — the liver cancer hepatoma, a potential complication of the hepatitis B virus.

- A measles-mumps-and-rubella combination vaccine that marked the first time vaccines for different viruses were successfully combined in a single shot.

- Vaccines for meningitis and pneumonia.

- A mumps vaccine that was the product of Hilleman's alertly isolating the virus by swabbing the back of his daughter Jeryl Lynn's throat the night she was stricken with the disease (50 years later it is still the basis for most mumps vaccines).

"Unlike many scientists who understand the leaf on the tree, he understood the whole forest."

David M. Morens

Hilleman also gave the world a more complete understanding of the ways different strains of the flu change slightly from year to year, a phenomenon known as genetic, or antigenic, drift. The need for an annual seasonal flu vaccine is due to these ongoing and subtle changes — not to be confused with the major changes in influenza viruses known as antigenic shift, which often mark the beginning of the less frequent but more deadly influenza pandemics.

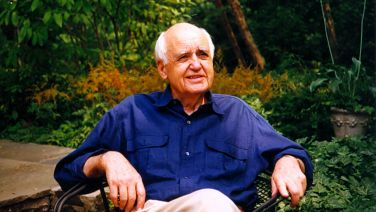

His 2005 obituary in The New York Times credits Hilleman with probably saving more lives than any other scientist in the 20th century.

In 2002, an 82-year-old Hilleman published a paper about influenza that pulled together all the known ideas on the epidemiology of influenza.

Hilleman consistently showed that he saw very complex things with astonishing clarity, said David M. Morens, a senior adviser to the director of National Insitutues of Health's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in a 2011 interview.

"Unlike many scientists who understand the leaf on the tree, he understood the whole forest," Morens said. "And, of course, he also understood the leaf. He was one of the premier vaccinologists of the 20th century, and he really was a big picture guy."

More than anything, Hilleman's paper had artistry in its description of theories he developed years earlier about how flu recycles certain components over time while waiting out a generation of human beings who have developed immunities.

"What he was describing is like a dance between the virus and the human population," Morens said. "As the generation that's been exposed to a certain strain of pandemic influenza dies off, there is an opportunity for a new strain of the virus, which has been absent over the years, to come in and infect the human population."

In 1957, Hilleman identified an outbreak of pandemic influenza in Hong Kong, saving millions of lives and defining his understanding of the disease.

Hilleman discovered that the only people with traces of immunity to this new virus had been alive long enough to have survived a pandemic that killed six million people worldwide in 1889-90.

Hilleman, who was then working with an influenza team at Walter Reed Army Medical Research Institute, raised the alarm about an impending pandemic.

"Not only did he believe that the virus circulating in Hong Kong — now called Asian flu — would spread throughout the world, but also he believed that it would enter the United States in the first week of September 1957," Offit writes in Vaccinated.

His prediction was right on the mark. Fortunately, thanks partly to Hilleman's persistence and fast-tracking production of 40 million doses of Asian flu vaccine, the pandemic was far less deadly than the infamous 1918 outbreak of Spanish flu.

According to Offit, the episode marks the only time in history that a scientist has correctly predicted an outbreak of pandemic influenza.

In recognition of his achievements, he received numerous honorary degrees, including an honorary doctorate in science from MSU in 1966. He was given the National Medal of Science by President Ronald Reagan. In 1999 Hilleman was invited to include some of his vaccines in a time capsule representing the greatest achievements of the 20th century.

At Merck, where Hilleman spent 30 years, seven of his vaccines are still in production. In 2008, the pharmaceutical giant named its Durham, North Carolina, vaccine research facility after Hilleman. Merck also funds the annual Maurice Hilleman/Merck Award, a $20,000 grant given by the American Society for Microbiology for outstanding research in vaccinology. At MSU, Hilleman endowed a speaker series, now named in his honor.

"Vaccines continue to have a major impact on public health across the globe--protecting health and saving millions of lives," said Julie L. Gerberding, president of Merck's vaccine division. "There is no doubt in my mind that much of this incredible impact on human life can be attributed to Maurice Hilleman, the father of modern-day vaccines."

While Hilleman's vaccines sent many once-common childhood diseases into relative obscurity in developed countries, Hilleman's legacy at times has appeared under siege by allegations from a vocal anti-vaccine movement that vaccines cause developmental harm in children. The most common charge is that the measles-mumps-rubella, or MMR, vaccine has been linked to autism.

"There is no doubt in my mind that much of this incredible impact on human life can be attributed to Maurice Hilleman, the father of modern-day vaccines."

Julie L. Gerberding

For those inclined to distrust modern medicine, it doesn't matter that British surgeon Andrew Wakefield's so-called smoking gun study linking MMR to autism in children has been discredited as fraudulent, Offit said. That is especially true in the age of the Internet, when the bad information travels as fast as the good.

"People are motivated by fear more than reason," Offit said. "And they can often find false information on the Internet that gives them a sense that they are part of a larger community than they really are."

Coming late in Hilleman's life, the controversy over MMR was disheartening for a man who set a goal of eradicating once-common childhood diseases.

During the 70-plus hours Offit spent interviewing Hilleman for Vaccinated — he called it the world's best crash course in vaccinology — Offit said a dying Hilleman fretted over the fear that prevents people from protecting their children.

"Here was this extremely rational, science-driven man and he couldn't understand," Offit said. "I can remember him looking out the window of his office and shaking his head, asking: 'Can't we learn from history? Do we really need to sacrifice our children to learn these lessons?'"

With some high-profile outbreaks of whooping cough raising awareness about childhood diseases and stirring fears of infection, Offit said he sees the pendulum swinging back in the debate.

Lorraine Hilleman agreed that the debate often comes down to awareness. "It is a testament to Maurice that many of these people doubt because they aren't familiar with how scary these diseases can be," she said.

Among those in the scientific community there is little doubt.

Given his humble roots and the keen pragmatism he grew up with--Hilleman often credited the chickens he raised as a child with his successful use of chicken eggs for vaccine development--Lorraine Hilleman said she hopes her husband is also remembered as being one other thing: "A Montanan."

Originally published in Mountains & Minds magazine, Fall 2012