Will weeds spread to higher elevations with a changing climate? The story for Dalmatian toadflax- July 2014

Download this weed post on climate change and Dalmatian toadflax as a PDF

Whether we like it or not, our climate is changing: generally Montana is getting warmer and patterns of precipitation (amount, form -snow or rain, timing) have changed in various ways across the state. In addition, the human population continues to grow in many parts of Montana, and this has increased the frequency and intensity of road and trail use. Understanding how weeds respond to such changes and where new populations are likely to occur is helpful for planning weed management at the broader scale. Dalmatian toadflax, originally from Eurasia, has been present in southwest Montana since the early to mid-1900s and occurs in a range of areas including our more mountainous areas. Weeds respond to disturbance and are more abundant on bareground than in healthy growing vegetation, which is why they are abundant along roadsides. So what is stopping the spread of this and other species to higher elevations and away from roads and trails? Are seeds not getting there? Is the climate so inclement that seeds arriving at higher elevations cannot germinate or establish? Or, does the intact high-elevation vegetation stop the invasion?

Field study

Researchers from Montana State University established sites throughout the current elevation range (5250-7550’) of Dalmatian toadflax in the Paradise Valley of Park County, MT, and into the northern range of Yellowstone National Park. We sampled along an elevation gradient to obtain different climate conditions: as a general rule a 300’ increase in elevation equals a 1-2O F decrease in temperature. We monitored the abundance (density and cover) and seed production of Dalmatian toadflax as well as various characteristics of the surrounding vegetative community for five years.

Results

The presence of Dalmatian toadflax was influenced by elevation, with the greatest chance of populations establishing in the middle of the elevation range (5900’) where the temperature was moderate and precipitation higher than at the lower sites (5250’). However, once a seedling became established at a site the resulting abundance of a population was not affected by elevation. In addition, the growth of populations (e.g. vegetative and flowering stem density, seed production) was similar along the elevation gradient, but the most successful populations were at sites with the highest bareground and lowest vegetation and litter cover, and tended to be in drier sites. The least successful populations were observed at sites with the lowest winter temperatures and more persistent soil moisture.

Management implications

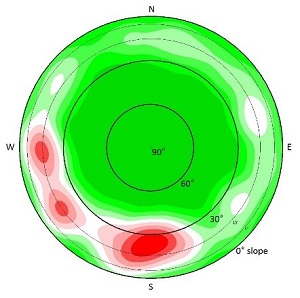

We found more Dalmatian toadflax on south through westerly aspects and on medium to steeper slopes. (Green = low occurrence; white through to dark red = higher occurrence. Slopes over 60o were not assessed.)

Dalmatian toadflax is a broadly adapted species, and we have no conclusive evidence that established populations are climatelimited, nor that seed availability is limited at higher elevations. Therefore, established populations have the potential to spread, particularly on steeper south to west facing slopes where the soil is disturbed and other vegetation is sparse. However, we do have evidence that establishment of new populations from seed is rare and dependent on site and climate characteristics. Overall, a warmer climate could increase the establishment of new populations on disturbed sites, but the spread of such populations away from roadsides will be strongly influenced by the surrounding vegetation – with less success at sites with abundant vegetation.

Read more by clicking the links below:

Pollnac F and Rew LJ (2013) Life after establishment: factors structuring a successful mountain invader away from disturbed roadsides. Biological Invasions.

Pollnac F, Maxwell BD, Taper M and Rew LJ (2013) The demography of native and non-native plant species in mountain systems: Examples

in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Population Ecology.