Eastern Heath Snail

The tiny terrestrial snail invading Central Montana

The Eastern Heath Snail (Xerolenta obvia) is a tiny invasive land snail that’s gaining

a foothold in Montana that could result in big impacts to the state. This dime-sized

terrestrial snail is native to central Europe and the Mediterranean and has been found

in three locations in North America: Detroit, Michigan; southern Ontario, Canada;

and central Montana.

The Eastern Heath Snail (Xerolenta obvia) is a tiny invasive land snail that’s gaining

a foothold in Montana that could result in big impacts to the state. This dime-sized

terrestrial snail is native to central Europe and the Mediterranean and has been found

in three locations in North America: Detroit, Michigan; southern Ontario, Canada;

and central Montana.

Like other nonnative species, Eastern Heath Snails (EHS) can thrive in a new environment where there are no predators to keep their population low nor competitors for the resources they need to survive.

Not much is known about how EHS got to Montana, but it is speculated they arrived in the early 1910s, possibly on equipment that was brought for mining operations near Belt. In 2012 the snails were “discovered” and identified as an invasive species to Montana.

Researchers have determined that Montana’s snails did not come from the Michigan or Ontario populations, as they have genetic differences. The snails in Ontario were first identified in 1969 and are likely the source for the snails that were detected in Michigan in 2001. Both the Michigan and Ontario EHS are found at industrial sites and rail yards near an international port. EHS are known to attach themselves to shipping containers, rail cars, and stone tiles.

In Montana, EHS thrive in dry, open, grassy areas; populations can be found along roadsides and in range and crop lands in Cascade, Chouteau, Judith Basin and Fergus counties. EHS are found in the city of Great Falls, a forested area near Monarch, near Highwood, and along MT Highway 87 between Belt and Stanford. The most recent detection of EHS was in Lewistown in 2023.

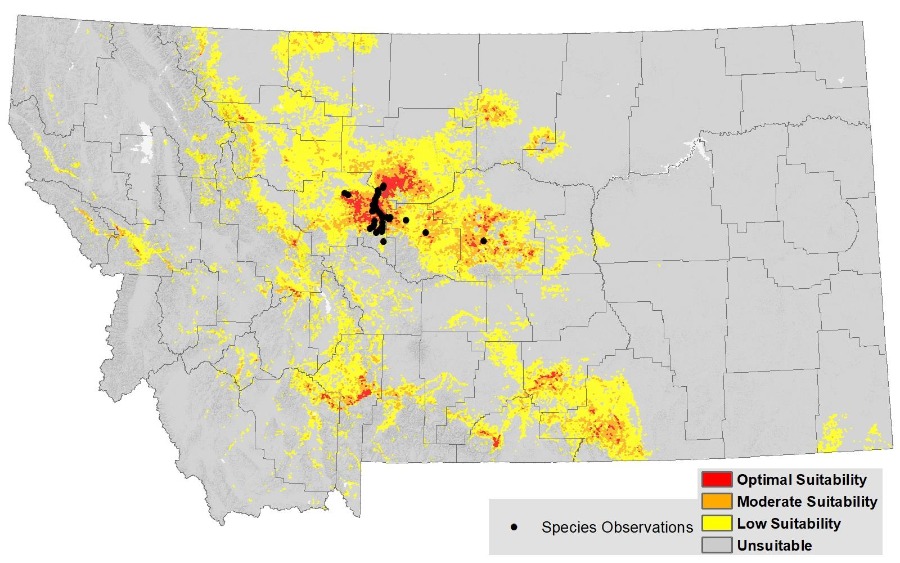

The Montana Natural Heritage Program provides a habitat suitability model that identifies the areas where EHS can successfully live and reproduce (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Habitat suitability in Montana. Observations used for modeling are displayed for reference. Source: Montana Natural Heritage Program. 2025. Eastern Heath Snail (Xerolenta obvia) predicted suitable habitat model. Montana Natural Heritage Program, Helena, MT.

Montana State University is conducting research to determine the snail’s basic biology and life cycle, egg production and deposition, predation and mortality factors, and what they prefer to feed on.

Studies indicate that snails may take two or more years to mature. EHS are hermaphroditic and can self-fertilize, which allows a lone snail to single-handedly populate an area. They lay a clutch of tiny white eggs in about two centimeters of soil, with anywhere from a few to 80 eggs per clutch. MSU field studies have found eggs are laid in the spring and fall after moisture events.

Montana has snail species that look very similar to EHS. However, EHS have a unique behavior that sets them apart from native snails. On hot summer days, EHS will attempt to escape hot temperatures on the ground by climbing up vegetation, fenceposts, hay bales, or any upright objects. This behavior is called “massing,” when several snails will climb and share elevated space. The snails then go into a period of “aestivation,” or dormancy, where they withdraw into their shell and seal the opening with a mucus membrane, waiting for better conditions. These snails might look dead, but they’re not.

Photo: Ian Foley, Montana Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org

EHS can impact agriculture production in a few ways. They feed on plants and detritus, but have an affinity for pulse crops like peas, lentils, and chickpeas. Contaminated crops would be costly to clean and could impact Montana’s export markets for these products.

A study conducted by the University of Montana’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research in 2022 determined the potential economic impact to Montana agriculture at $1.4 million per year for mitigation and post-harvest processing costs for a variety of crops.

Snails can cause issues with mechanical harvesting of crops and alfalfa when large numbers of crushed snails gum-up harvesting equipment; snail goo sets up like concrete when it’s dry. EHS are potential vectors for some plant and animal diseases such as sheep lungworm.

A group of invasive terrestrial snails comparable to EHS were introduced to Australia over 100 years ago. Since the 1990s, ag producers in southern Australia have battled these snails which have become major pests of grains, horticulture, grapes and pasture. Australia has developed the integrated snail management program called “Bash’Em, Burn’Em, Bait’Em.” This three-pronged approach to snail control gives landowners some options.

Snails move at (you guessed it) a snail’s pace. But they can travel long distances when hitchhiking on items transported by humans. It only takes one snail to colonize a new area.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR:

|

If you live in a county where EHS are found, carefully check materials or equipment before transporting. If EHS are found, they should be removed and “bashed” or crushed. EHS have been found on items like lawn mowers, propane tanks, fencing materials, construction equipment, barbeques, bee hives, ATVs, and hay bales. Crushing the shell is the best way to ensure a snail is dead. Never move soil or gravel from infested areas as it can harbor snails and their eggs.

Landowners can help manage EHS by removing trash and litter that provide snails with hiding places. Debris that is free of snails should be bagged, sealed and disposed of in municipal trash. Materials with snails should not be transported. If snails are present, they should be removed and crushed.

Mowing vegetation to five inches or less eliminates their ability to climb and mass on vegetation. Modifying a site by raking, grading, rolling, or resurfacing with crushed stone or gravel will ensure shells are crushed and help to eliminate their habitat.

Photo: Anonymous submission to the Montana Department of Agriculture

When safe to do so, burning an infested site is another method of control. Make sure to follow local burn ordinances when using this option.

Snail bait or molluscicides with iron phosphate can create barriers around gardens or homes to exclude snails, but these products don’t provide a viable solution to large scale infestations. Apply molluscicides that are approved for Montana and use according to the label.

Snails are easy to overlook, but when you know what you’re looking for, it’s easy to spot EHS. Preventing EHS from hitching a ride to new areas and early detection of this invasive snail are our best defense to stop their expansion in Montana. Report sightings of EHS to a local MSU Extension office or the Montana Department of Agriculture at 406-444-9066.

REFERENCES AND MORE INFORMATIONMontana Invasive Species Council – Eastern Heath Snail (Science advisory panel report, economic report, videos, fact sheet, and other resources) |

Liz Lodman is the Administrator of the Montana Invasive Species Council.