Nepal Instructional Resources

Table of Contents

Mary Sellars

Kim Busch

-

Reflection

-

STEM Learning Opportunities in the Himalayas

-

Lesson Plan 1: The Formation of the Himalayas

-

Lesson Plan 2: Analyzing the Impact of Tectonics

-

Lesson Plan 3: Analyze Fossil Evidence

-

Lesson Plan 4: Factors Affecting Climate in the Himalayas

Victor Lorenz

-

Reflection

-

Lesson Plan 1: Consequences of Climate Change

-

Lesson Plan 2: Analyzing Plate Tectonic Forces in the Formation of the Himalayan Mountain Range

-

Lesson Plan 3: Analyzing the Implications of Glacial Runoff in the Himalayan Mountains for Hydroelectric Production

-

Lesson Plan 4: Analyzing the Socio-cultural Consequences of Tourism in the Himalayas on the Sherpa Community

-

Embarking on a Geological Exploration: Nepal Evening Geology Talk

Kaitlin Murphy

Donna Tully

Greg Anderson

Jessica Chute

-

Reflection

-

Lesson Plan 1: Blood Oxygen Concentration Variance by Elevation

-

Lesson Plan 2: Boiling Time of Water at Different Elevations

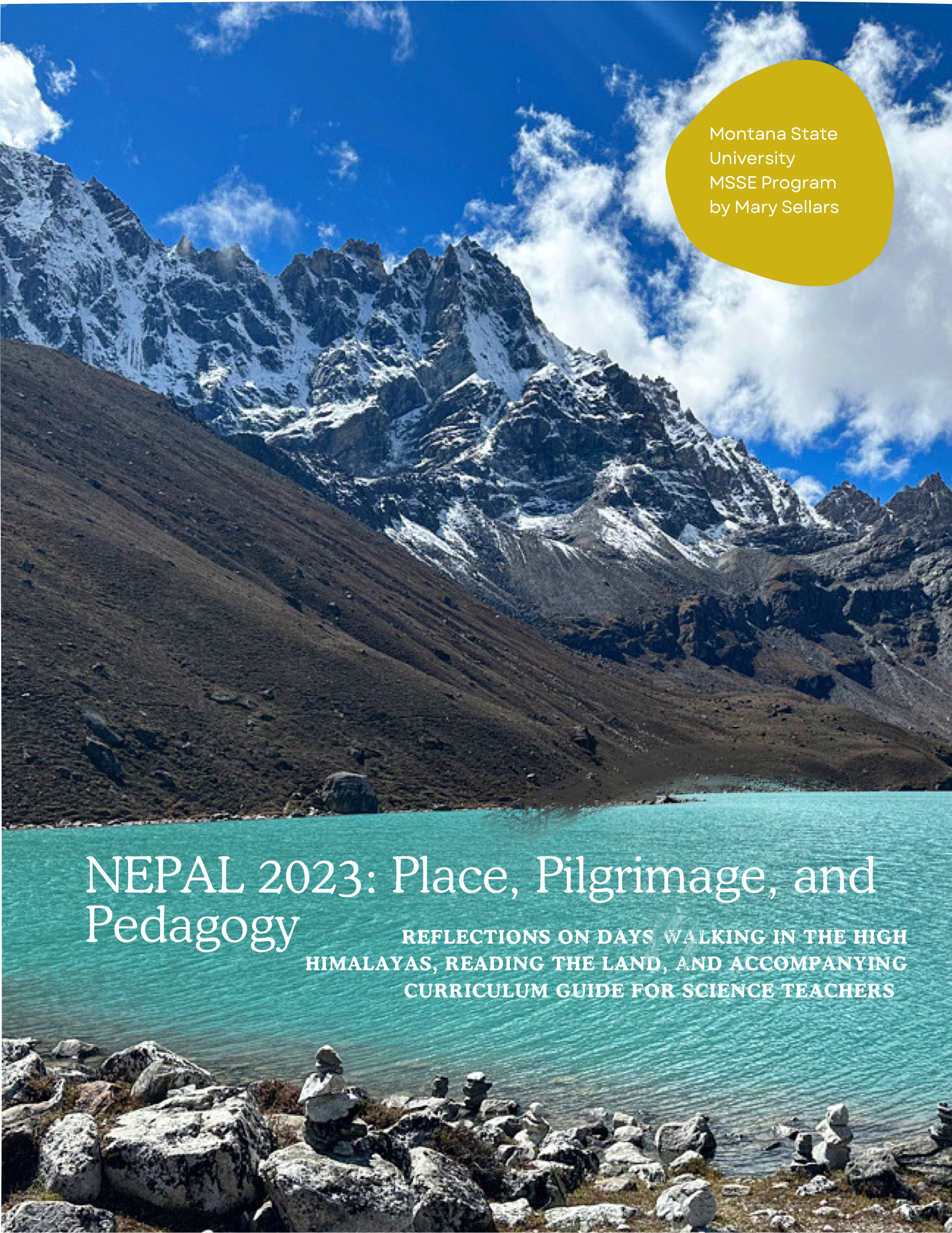

Mary Sellars: Nepal Curriulum Guide and Handbook

Kim Busch: Reflection

The Nepal School System

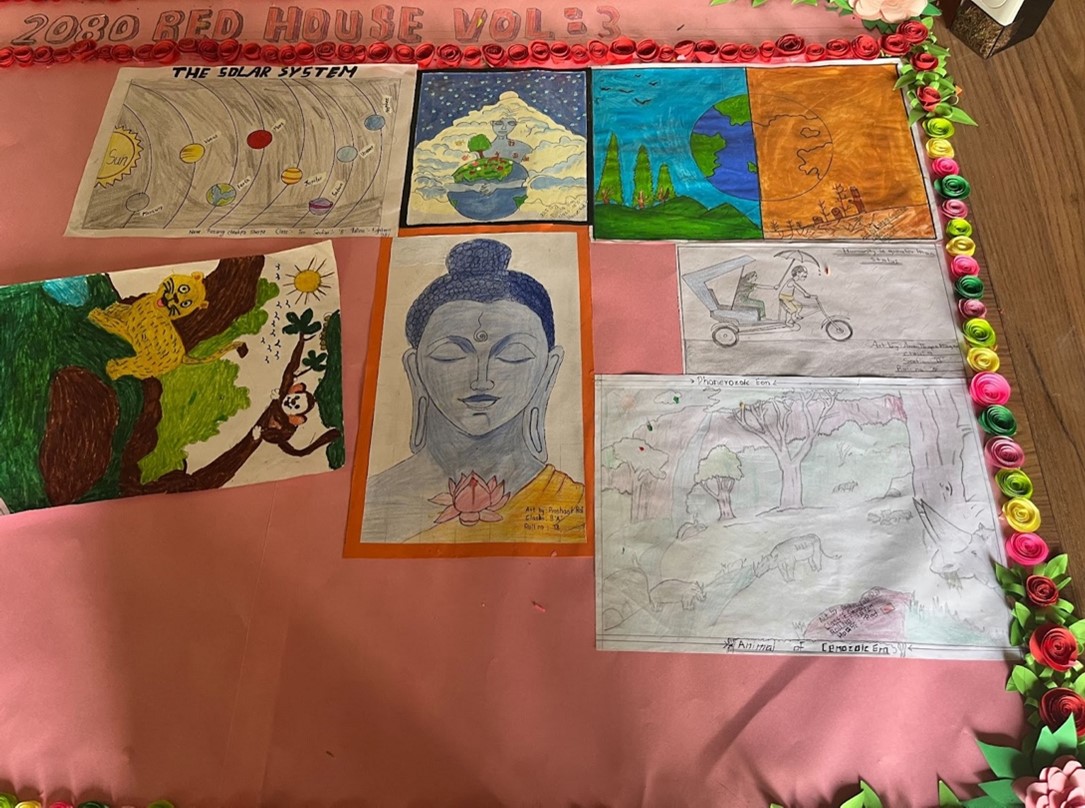

I am not sure what I expected from schools in Nepal, but it wasn’t really what we saw. The elementary school seemed very “British”. The students wore uniforms and sat at wooden desks organized in rows, much different from modern American early childhood classrooms.

American early childhood teachers create cozy, “cute” learning spaces with round tables, small chairs, and a large area, usually carpeted or with a large rug, for whole-group instruction. Most have numerous areas set up for small group instruction and center work. They usually have classroom libraries full of books for students to use. The walls are covered with learning posters and student art. I did not notice those types of items in the classroom we visited.

But what I did notice was that the Nepalese early childhood classrooms had teacher-made handwritten labels for many everyday items. All the labels were in English. Students in Nepal start learning English in first grade. The Nepalese people value speaking English as well as Sherpa and Nepalese.

In the United States, we have used the school system to remove language from entire groups of people. Even after we stopped putting Native students in boarding schools and punishing them for speaking their native language, we continued to discourage families from speaking two languages. Many Speech teachers blamed speech problems on the family because they spoke a different language at home. It wasn’t until recently that Americans started valuing the ability to be able to speak more than one language.

The older students' classrooms seem to be very basic. I don’t actually remember if there were learning posters or decorations, Again, most of the instruction seemed to be in English. Some students were more comfortable speaking English and talking in front of a group of people.

Surprisingly, the primary school near Lukla had a large computer lab. There were at least 30 Dell desktop computers. All these donated machines were packed in by humans or animals. All those monitors and CPUs would draw a lot of electricity. It is a challenge for the school to generate enough electricity to operate the lab. It is obvious that the community values their students developing computer skills. It would be nice if they could use laptops or Chromebooks, but what are they going to do with all the electronic equipment when it is out of date?

Students were working with a textbook on how to use the Windows operating system. In my school, the only students who get basic computer skill instruction are 6th graders who do not take Band, Orchestra, or Choir. So, out of 230 students, about 30 of them get this instruction during the second semester.

I assume that the school near Lukla has internet service, but I don't know at what level or if the students can access it. I would guess it is limited since we weren’t always able to access Wifi, and it was unreliable. I do not know if that is a pro or a con.

My students and I are heavily dependent on internet access, to the point that I will use the hotspot on my phone if I lose connectivity. My students demonstrate addictive behaviors in regard to any type of game. I think we, Americans, have lost a connection to each other and the natural world because of our reliance on the internet.

During a class visit, we asked one of the older students about what he would like to do after high school. He expressed that he would like to come to the United States. I forgot what a fantastic country we live in and that people view it as a place with tremendous opportunities for a better life. It is easy to be disillusioned by current political issues and public opinion of the educational system.

Another significant difference between the school systems in America and Nepal is parent and community expectations. Nepalese parents expect the school to provide basic academic instruction. Many American parents or society expect their children to receive much more. For many students, the school system provides two meals, social and emotional support, and mental health services, on top of academics.

Both, the American and Nepalese school systems, have some form of academic testing. My research suggests students take a Secondary Education Examination (SEE) at the end of grade 10. The exam includes English, Nepali, mathematics, science, social studies, and optional subjects based on the students' selected path of study. From there, they often have to leave their homes to pursue higher education in Kathmandu.

In the United States, we begin standardized testing as early as 3rd grade. A great deal of pressure is placed on elementary school teachers to have students test at proficient or advanced levels. Students may receive remediation courses based on their scores. In my district, at the middle school level, students begin to be placed in leveled math and English classes based on those scores. Advanced students then have access to enriched or higher-level courses, but struggling students often have to take remedial classes instead of electives.

Class sizes were notably smaller in the Nepalese schools we visited. The rooms we visited had about 10 to 12 students. These schools seemed to have a lot of students, so I am assuming it was a school decision to have smaller class sizes. I was unable to find any information about government-mandated class sizes in Nepalese schools. It is more likely that class size depends on location, infrastructure, and population. In Montana, Kindergarten, first and second grade should be 20 or fewer, but jump to 28 for 3rd and 4th grade. Fifth grade and up can have up to 32 students. Of course, in our rural areas, classes would be significantly smaller because of population density.

In conclusion, the Nepalese schools were very traditional but also very valued. I wish we as Americans would realize how lucky we are to have neighborhood schools with highly qualified teachers.

Kim Busch: STEM Learning Opportunities in the Himalayas

With the help of ChatGPT 3.5, I explored the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) learning opportunities related to the Himalayan mountains and found there to be significantly more than I first realized. ChatGPT suggested that “integrating the study of the Himalayan ecosystems into STEM education provides an opportunity for students to understand the interconnectedness of environmental, geological, and human systems, fostering a holistic approach to scientific inquiry and problem-solving.” I agree and would add that would integrates well with Social Studies as well. Using the AI suggestions, I researched the topics and aligned them with the Next Generation Science Standards for Middle School and Middle School Social Studies Standards.

The Himalayas' location and geology create a unique and diverse ecosystem. The Himalayas are some of the youngest mountains in the world. They were created by the collision of the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates. The collision between the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate has led to the dramatic upliftment of the Himalayan region. The Himalayas are still rising today at a relatively slow rate. The uplift is not uniform, and different segments of the mountain range are rising at different rates. This ongoing convergence results in significant seismic activity in the region. Earthquakes are common, and the Himalayan region is known for its seismic hazards.

The Himalayas cover about 1500 miles (2400 km) at approximately 28 degrees North of the equator, the same latitude as the southern United States. The area ranges from tropical to perennial snow and ice, depending on the elevation. The outer edge of the Himalayan range (1,650 ft. to 3,300 ft.) includes tropical and subtropical broadleaf forests and a number of threatened species, including the Asian elephants. Middle elevations (6,600 ft. to 9,800ft.) of the eastern region have temperate broadleaf and mixed forest. These forests can receive up to 80 inches of precipitation. The wide range of wildlife includes numerous types of birds and the golden langur monkeys. In the northeastern Himalayas (8,200 to 13,000 ft.), there is a temperate sub-alpine conifer forest with red pandas, takin, and mush deer. The alpine shrubs and grassland make up the area from 9,850 to 16,400 feet. This area has mild summers and cold winters. It is also the home to the snow leopard, Himalayan tahr, musk deer, and pikas. The complex topography of the region has led to the evolution of numerous specifics that are not found anywhere else in the world. The snow line occurs at about 16,000 feet, creating harsh conditions with little to no vegetation.

The Himalayan mountain range plays a crucial role in influencing the weather and climate of the surrounding region. During the winter months, the Himalayas act as a barrier to the movement of cold air masses from the north. This barrier prevents the cold, dry air from entering the Indian subcontinent. During the summer, the intense heating of the Indian subcontinent draws moist air from the Indian Ocean. As this moist air rises, it encounters the Himalayas, causing it to cool and release heavy rainfall on the windward side of the mountains.

The Himalayas are home to the world's third-largest deposit of snow and ice, including approximately 15,000 glaciers. During the warmer months, glacier melting contributes to water flow into major river systems, including the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Indus. These rivers play a vital role in supporting agriculture and ecosystems in the surrounding plains.

The Himalayas play a role in global atmospheric circulation. The interaction between the atmosphere and the high mountain range contributes to the dynamics of the Asian monsoon system, which, in turn, influences global weather patterns.

Lesson Topics: Mountain Geology and Ecosystems

- Students will discover how the geological processes shape the landscape. (MS-ESS2-2)

- Students will examine the geological features of the Himalayas and their influence on the diversity of ecosystems. (MS-LS2-2)

- Students will discuss how geological processes shape the landscape and affect the distribution of flora and fauna. (MS-LS2-1)

- Students will learn about flora and fauna's adaptations to the Himalayas' high-altitude environment. (MS-LS2-2)

- Students will learn about the monsoon season in the Himalayan region and how it influences weather patterns. (MS-ESS3-6)

Lesson Topic: Natural Hazards and Disaster Resilience:

- Students will examine the natural hazards caused by the tectonic movement that affect the Himalayan region, such as earthquakes, landslides, and avalanches. (MS-ESS2-2)

- Students will review and develop strategies for building resilience in ecosystems and human communities in the face of these hazards. (MS-LS2-5, MS-ESS3-2, SS.G.6-8.4, 8.5, 8.6)

Lesson Topic: Himalayan Forests and Wildlife Conservation:

- Students will study the forests of the Himalayas and their importance for wildlife habitat. (MS-LS2-2, MS-LS2-3, MS-LS2-4)

- Students will explore conservation initiatives aimed at protecting endangered species, like the snow leopard and red panda. (MS-LS2-5)

Lesson Topic: Biodiversity in the Himalayan Region:

- Students will explore the rich biodiversity of the Himalayan ecosystems, including the variety of flora and fauna that inhabit different altitudes.(MS-LS2-1)

- Students will research and discuss the role of the Himalayas as a biodiversity hotspot and the importance of conservation efforts.(MS-LS2-4)

- Students will understand the diverse climate zones in the Himalayas and explore how elevation influences temperature and precipitation. (MS-ESS2-5, MS-ESS2-6)

Lesson Topic: Climate Change Impact on Himalayan Ecosystems:

- Students will research the effects of climate change on the Himalayan region, such as changes in temperature, glacial retreat, and altered precipitation patterns.(MS-ESS3-5, MS-ESS2-6)

- Students will use research to predict the implications for ecosystems, including potential shifts in vegetation zones and impacts on wildlife.(MS-LS2-4, MS-ESS3-5)

Lesson Topic: Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Himalayan Communities

- Students will research the traditional ecological knowledge of indigenous communities living in the Himalayan region and compare it to the indigenous knowledge of other regions. (SS-G.6-8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 8.6)

- Students will research and discuss how local communities adapt to and sustainably manage the unique ecosystems of the mountains.(MS-ESS3-5)

- Students will investigate the cultural and spiritual significance of the Himalayas in local communities. (SS-G.6-8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 8.6)

- Students will explore how these values contribute to conservation efforts and sustainable practices. (MS-ESS3-5)

Lesson Topic: River Systems and Watersheds:

- Students will study the major river systems originating from the Himalayas, such as the Ganges, Indus, and Brahmaputra. (MS-ESS2-4)

- Students will explore the importance of these rivers in sustaining ecosystems downstream and the challenges they face due to human activities.(MS-ESS3-3, SS-G.6-8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 8.6)

Lesson Topic: Glacial Melt and Water Resources

- Students will investigate the impact of glacial melt on water resources in the Himalayan region. ((MS-LS2-3, MS-ESS3-3)

- Students will research the role of glaciers in providing freshwater and the potential consequences of glacial retreat on downstream ecosystems and human communities. (MS-LS2-3, MS-ESS3-3, SS-G.6-8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 8.6).

References

fultonk. (2011a, February 11). The Himalayas ~ Himalayas Facts | Nature | PBS. Nature. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/nature/the-himalayas-himalayas-facts/6341/

fultonk. (2011b, February 11). The Himalayas ~ Tectonic Motion: Making the Himalayas | Nature | PBS. Nature. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/nature/the-himalayas-tectonic-motion-making-the-himalayas/6342/

Hatch, R. (2015, February 9). The Weather and Climate of the Himalayas. HimalayanWonders.com. https://www.himalayanwonders.com/blog/weather-climate-himalayas.html

Himalayas. (2023). Britannica Kids. https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/Himalayas/274884

MONTANA CONTENT STANDARDS FOR SOCIAL STUDIES FOR K-12. (n.d.). Retrieved December 3, 2023, from https://opi.mt.gov/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=z2KzgjyQYtY%3D&portalid=182

MS-ESS2 Earth’s Systems | Next Generation Science Standards. (2023). Nextgenscience.org. https://www.nextgenscience.org/dci-arrangement/ms-ess2-earths-systems

MS-ESS3 Earth and Human Activity | Next Generation Science Standards. (2023). Nextgenscience.org. https://www.nextgenscience.org/dci-arrangement/ms-ess3-earth-and-human-activity

MS-LS2 Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and Dynamics | Next Generation Science Standards. (2023). Nextgenscience.org. https://www.nextgenscience.org/dci-arrangement/ms-ls2-ecosystems-interactions-energy-and-dynamics

Kim Busch: Lesson Plan 1

Title: The Formation of the Himalayas: Exploring Plate Tectonics

Lesson Outline generated with Eudaide.ai and modified and enhanced by Kim Busch

Grade Level: Middle School (Students Grade 6-8)

Time: 45-52 minutes

Objective: Students will explain the primary geological process responsible for the movement of the Indian Plate towards the Eurasian Plate, leading to the formation of the Himalayas.

Key Vocabulary:

- Plate tectonics

- Continental drift

- Convergent boundary

- Subduction

- Collision

- Fold mountains

Materials:

* Images of Mt. Everest

* World map or globe

* Large paper or whiteboard

* Markers

* Handouts with diagrams of plate boundaries

* Internet access or other resources (YouTube resources, articles from National Geographic) about the formation of the Himalayas

Procedure:

Engage (5 minutes):

- Begin the lesson by showing an image of Mt. Everest.

- Ask the students if they have ever wondered how mountains like the Himalayas were formed.

- Facilitate a brief discussion to generate curiosity and activate prior knowledge about plate tectonics.

Explore (10 minutes):

- Divide the class into groups of 3-4 students.

- Distribute handouts with diagrams of plate boundaries.

- Instruct each group to examine the diagrams and discuss the different types of plate boundaries.

- Encourage students to identify the type of boundary that exists between the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate.

Explain (10 minutes):

- Bring the class back together and ask each group to share their findings.

- Discuss the concept of convergent plate boundaries and explain how they are responsible for the formation of mountains.

- Provide a brief overview of the movement of the Indian Plate towards the Eurasian Plate and the geological processes involved.

- Have students watch an introductory video about plate tectonics (Paul Anderson's Bozeman Science Video)

- Facilitate a class discussion to ensure understanding and address any questions.

Elaborate (15 minutes):

- Divide the class into pairs and provide each pair with internet access and a variety of predetermined links.

- Instruct students to conduct research on the geological processes involved in the formation of the Himalayas.

- Encourage students to take notes and gather information to support their understanding of the topic.

- Circulate the classroom to provide assistance and monitor student progress.

Evaluate (10 minutes):

- Ask each pair of students to prepare a short presentation summarizing their research findings.

- Provide time for the presentations and encourage questions and discussions.

- Assess student understanding throughout the presentations and provide feedback.

Closure (2-5 minutes):

- Summarize the key points discussed during the lesson.

- Emphasize the primary geological process responsible for the movement of the Indian Plate towards the Eurasian Plate, leading to the formation of the Himalayas.

- Encourage students to reflect on their learning and ask any remaining questions.

Options for Differentiation:

- For students who need additional support, provide simplified diagrams and explanations.

- For advanced students, encourage them to explore additional geological processes involved in mountain formation beyond the Himalayas.

- Provide English language learners with visual aids and vocabulary support. (Informational text reading levels differentiated by Differ.)

Assessment of Learning:

- Observe student participation and engagement during discussions and group work.

- Assess student understanding through their contributions to the class discussion.

- Evaluate the quality of the presentation and the accuracy of information shared by each pair of students.

Kim Busch: Lesson Plan 2

Title: Analyzing the Impact of Tectonic Movement on Natural Hazards in the Himalayan Region

Grade: Middle School (Students Grade 6-8)

Lesson Outline generated with Eudaide.ai and modified and enhanced by Kim Busch

Duration: 45-52 minutes

Objective: Students will analyze the geological phenomenon of tectonic movement in the Himalayan region, focusing on its impact on natural hazards, including earthquakes, landslides, and avalanches.

Materials:

- Interactive whiteboard or projector

-Video of earthquake activity in Nepal

- Laptops or tablets with internet access

- Geological maps of the Himalayan region

- Images and videos depicting tectonic movement and natural hazards

- Chart paper and markers

Key Vocabulary:

- Tectonic movement

- Geology

- Himalayan region

- Plate boundaries

- Earthquakes

- Landslides

- Avalanches

- Natural hazards

- Seismic activity

- Epicenter

Background knowledge:

Prior to this lesson, students will have completed lessons about plate tectonics and the specific interactions between the Indian and Eurasian plates that created the Himalayan mountains. The ongoing tectonic activity results in current events, including earthquakes, landslides, and avalanches.

Procedure:

Engage (10-12 minutes):

- Begin the lesson with a short video about the 2015 Earthquake in Nepal.

- Ask students to share their initial thoughts and observations about why this happened.

Explore (10-12 minutes):

- Have students use their devices in pairs or small groups to watch different videos explaining earthquakes.

- Students then write their definitions of earthquakes.

- Each group presents their definition.

Explain (10-12 minutes):

- Using the interactive whiteboard or projector, present a geological map of the Himalayan region.

- Explain the concept of plate boundaries and how they relate to tectonic movement.

- Discuss how tectonic movement in the Himalayan region leads to natural hazards such as earthquakes, landslides, and avalanches.

- Show images and videos of these natural hazards occurring in the region to provide visual context.

- Facilitate a class discussion, allowing students to ask questions and share their observations.

Elaborate (10-12 minutes):

- Divide students into small groups and provide each group with a large sheet of chart paper and markers.

- Assign each group one natural hazard (earthquakes, landslides, or avalanches) to focus on.

- In their groups, students should brainstorm and list the causes, effects, and preventive measures related to their assigned natural hazard.

- Encourage students to collaborate and think critically about the information they have learned.

Evaluate (5-7 minutes):

- Have each group present their findings to the class.

- Encourage the class to actively listen and take notes on the other groups' presentations.

- Conclude the lesson with a closure activity where students summarize their learning by answering the following questions:

- What is tectonic movement and how does it impact the Himalayan region?

- What are some natural hazards caused by tectonic movement?

- How can people mitigate the impact of these natural hazards?

Options for Differentiation:

- Provide additional resources or simplified readings for struggling students.

- Pair students with different abilities during the Explore and Elaborate stages to facilitate peer learning.

- Offer extension activities for advanced students, such as researching other regions with significant tectonic movement and comparing their natural hazards.

Kim Busch: Lesson Plan 3

Title: Analyze fossil evidence found on Mt. Everest

Lesson generated with Eudaide.ai and modified/enhanced by Kim Busch

Grade Level: Middle School (Students Grade 6-8)

Duration: 45-52 minutes

Key Vocabulary:

- Fossil

- Geological history

- Ecosystem

- Adaptation

- Sedimentary rock

- Fossilization process

- Paleontologist

- Extinct

- Species

- Stratigraphy

Materials:

-Weather Channel Image and article: Why Are There Fish Fossils High Up in the Himalayas

-fossil replicas (or images)

-hand lens

Lesson Outline:

Engage (5-7 minutes):

- Begin the lesson by asking students if they know what fossils are and how they are formed.

- Show images of fossils found on Mt. Everest to generate curiosity and capture students' attention.

- Engage students in a brief class discussion about what they think the fossils found on Mt. Everest can tell us about the region's geological history and ancient ecosystems.

Explore (10-12 minutes):

- Divide students into small groups and provide each group with a set of fossil replicas, magnifying glasses, and hand lenses.

- Instruct students to closely observe and analyze the fossil replicas, discussing their observations within their groups.

- Encourage students to make connections between the fossils and what they already know about ancient life forms and geology.

Explain (10-12 minutes):

- Facilitate a whole-class discussion to share and compare the observations made by different groups.

- Introduce key vocabulary terms related to fossils and geological history.

- Explain the process of fossilization and how fossils can provide clues about ancient ecosystems and species that existed in the past.

- Use visual aids, such as diagrams or charts, to support student understanding.

Elaborate (10-12 minutes):

- Provide students with a reading passage or article about the fossil evidence found on Mt. Everest.

- Instruct students to read the passage individually or in pairs and identify key information related to the region's geological history and ancient ecosystems.

- Encourage students to annotate the text, highlight important details, and write down any questions they have.

Evaluate (5-7 minutes):

- Assess student understanding by conducting a short quiz or exit ticket that includes multiple-choice or short-answer questions about the lesson's content and key vocabulary.

- Alternatively, students can create a concept map or a visual representation of the connections between fossils, geological history, and ancient ecosystems.

- Use the assessment to guide future instruction and provide feedback to students.

Closure:

- Conclude the lesson with a brief class discussion, allowing students to share their key takeaways from the lesson.

- Summarize the main points of the lesson, emphasizing the importance of analyzing fossil evidence to understand the geological history and ancient ecosystems of a region.

Differentiation Options:

- Provide additional visuals, such as videos or interactive simulations, for students who may struggle with understanding the concept of fossilization.

- Offer advanced reading materials or research projects for students who demonstrate a deeper understanding of the topic.

- Pair students with different abilities together during the exploration and elaboration phases to foster collaboration and peer learning.

Assessment of Learning:

- Quiz or exit ticket assessing understanding of key concepts and vocabulary.

- Concept map or visual representation demonstrating connections between fossils, geological history, and ancient ecosystems.

Kim Busch: Lesson Plan 4

Title: Factors Affecting Climate in the Himalayas

Lesson Outline generated with Eudaide.ai and modified and enhanced by Kim Busch

Grade Level: Middle School (Students Grade 6-8)

Duration: 2 to 3 days with classes lasting 45-52 minutes

Key Vocabulary:

- Climate

- Himalayas

- Elevation

- Latitude

- Monsoon

- Orographic effect

- Albedo

- Topography

- Precipitation

- Temperature

Materials:

-Images of different ecosystems/climate zones in the Himalayas

-Climate data for different locations

-Maps and diagrams of the region

-Weather and Climate Data Resources

-Case study or scenario from the region

-Predetermined digital resources

Background Knowledge:

Students will already have a basic understanding of the different climate zones, the effect of direct and indirect sunlight, seasons, and altitudes effect on weather and/or climate.

Procedure:

Engage (10 minutes) :

-Begin the lesson by showing students a captivating image of the Himalayas and asking them to share what they know or think about the region's climate.

- Facilitate a brief class discussion to elicit students' prior knowledge and generate curiosity about the factors affecting climate in the Himalayas.

Explore (20 minutes) :

- Divide students into small groups and provide each group with a set of climate data for different locations in the Himalayas (e.g., temperature, precipitation, elevation, etc.).

- In their groups, students will analyze the data and identify any patterns or correlations they observe.

- Encourage students to discuss and share their findings within their groups.

Explain (20 minutes):

- Facilitate a whole-class discussion where groups can present their findings and discuss the factors they believe are influencing the climate in the Himalayas.

- Introduce and define key vocabulary related to the factors affecting climate in the Himalayas.

- Use visual aids, such as maps or diagrams, to help students visualize the concepts being discussed.

Elaborate (20 minutes):

- Provide students with a case study or scenario that requires them to apply their understanding of the factors affecting climate in the Himalayas.

- In their groups, students will analyze the given scenario and identify the specific factors at play.

- Encourage students to think critically and justify their reasoning using the key vocabulary introduced earlier.

Evaluate (15 minutes):

- As a formative assessment, ask students to individually write a short paragraph summarizing the main factors affecting climate in the Himalayas and how they interact with each other.

- Collect and assess the students' written responses to gauge their understanding of the topic.

Options for Differentiation:

- Provide additional support to struggling students by assigning them to mixed-ability groups where they can benefit from peer assistance.

- Offer a challenge task for advanced students that requires them to research and present on a specific factor affecting climate in the Himalayas.

Assessment of Learning:

- The written paragraph and class discussion will be used to assess students' understanding of the factors affecting climate in the Himalayas and their ability to explain the interplay between these factors.

Victor Lorenz: Reflection

NEPAL FIELD EXPERIENCE REFLECTION ESSAY

What started as an epic and incredible journey has now become nothing more than a monumental surreal memory. All the planning and preparation, the zoom meetings, the cross-fit training, the geologic research, the hype, it’s over. It’s sad, but I am so thankful for the opportunity. Thank you, John and thank you, Holly. Thank you, Krishma, and thank you to the guides and porters. A very special thank you to Sonam Tamang. I very much enjoyed my experience at the front of the group asking Sonam questions about Nepal and the peace I felt while trekking with him. I would also like to extend a special thanks to my peers for making my first trip abroad a memorable and enjoyable one. I look forward to doing more traveling abroad in the future.

The rich tapestry of interconnected societies, cultures, and environments encapsulates a complex web of relationships. As I delved into exploring these interconnected facets, I became acutely aware of the intricate interplay between individuals, communities, and the world at large. This reflection will delve into the profound implications of globalization on local communities and ecosystems while contrasting the educational landscapes of Nepal and the United States.

The interconnectedness between societies, cultures, and environments is a symphony that resonates across time and space. I realized that every cultural manifestation is intertwined with its environmental context. For instance, Nepal’s rich cultural heritage is deeply rooted in its breathtaking landscapes, echoing the symbiotic relationship between culture and nature. The personal interactions within these interconnected systems are the threads that weave the fabric of our shared existence.

The Sherpa culture, deeply rooted in the Himalayan region, stands as a testament to resilience, adaptability, and rich traditions. The influx of Westerners exploring the majestic Himalayas has engendered a unique interplay of cultures, offering a fascinating lens through which to explore the intersection of tradition and modernity. This paper aims to delve into the Sherpa culture while examining the dynamics and interactions between Sherpas and Western tourists amidst the backdrop of Himalayan expeditions.

The Sherpa people, renowned for their mountaineering prowess and revered as guardians of the Himalayas, possess a distinct cultural heritage deeply entwined with the mountains they call home. Their customs, language, and spiritual beliefs reflect a harmonious coexistence with the rugged Himalayan terrain. The Sherpas' reverence for nature, manifested in their religious practices and folklore, underscores their stewardship of the environment.

Moreover, the Sherpa community's communal lifestyle, characterized by strong familial bonds and collective responsibility, serves as a cornerstone of their society. The Sherpas' traditional practices, including yak herding, farming, and craftsmanship, are integral to their cultural identity, fostering a sense of pride and continuity in an ever-evolving world.

The allure of the Himalayas, with its towering peaks and mystique, has drawn countless Western adventurers seeking to conquer its summits or immerse themselves in its serene landscapes. The Sherpas, revered for their mountaineering expertise, have become indispensable companions to Western climbers and trekkers. Sherpa guides, porters, and support staff not only provide logistical assistance but also serve as cultural ambassadors, offering insights into their way of life and facilitating cross-cultural exchanges.

The interactions between Westerners and Sherpas during expeditions often transcend language barriers, fostering camaraderie and mutual respect. Westerners, often awestruck by the Sherpas' resilience and mountain skills, find themselves immersed in a culture that values humility, teamwork, and reverence for nature. Conversely, Sherpas benefit from exposure to Western perspectives, technology, and economic opportunities brought about by tourism.

However, the influx of Western tourism in the Himalayas poses challenges to the traditional Sherpa way of life. Rapid modernization, influenced by tourism and external influences, has led to shifts in values and cultural practices within the Sherpa community. The younger generation, exposed to Western ideas and aspirations, grapples with the tension between preserving their heritage and embracing societal changes.

Moreover, the commercialization of mountaineering and tourism has placed strains on the environment and local resources. Issues like waste management, over-tourism in certain areas, and the impact of climate change pose threats to the fragile Himalayan ecosystem, prompting discussions on sustainable tourism practices.

In conclusion, the interactions between Sherpas and Westerners in the Himalayas exemplify the intricate dance between tradition and globalization. While these encounters facilitate cultural exchange and economic opportunities, they also necessitate a delicate balance between preserving Sherpa heritage and adapting to a changing world. Embracing responsible tourism practices and fostering mutual understanding can pave the way for a harmonious coexistence between Sherpa culture and Western visitors, ensuring the preservation of the Himalayan legacy for generations to come.

Globalization, often portrayed as an indication of progress, is a double-edged sword. While it ushers in economic opportunities and cultural exchanges, it also leaves indelible footprints on local communities and ecosystems. Witnessing firsthand the transformations in local economies, I grappled with the dichotomy of progress and disparity. The rapid influx of global influences poses challenges to the preservation of indigenous cultures like the Sherpa and local identities, threatening the delicate balance between tradition and modernity. Moreover, the ecological footprint of globalization looms large, evident in the strain on ecosystems due to unchecked exploitation of resources.

The impact of globalization on Sherpa communities and ecosystems in the Himalayas has been profound, ushering in both opportunities and challenges that have significantly shaped their way of life and the fragile environment they inhabit.

Globalization has introduced economic opportunities to Sherpa communities through the growth of tourism and mountaineering expeditions in the Himalayas. Sherpas, renowned for their mountain expertise, have become integral to the tourism industry as guides, porters, and support staff for Western climbers and trekkers. This influx of tourism has provided employment and income sources for many Sherpas, contributing to the local economy.

However, this economic shift has led to changes in traditional livelihoods. While tourism offers financial benefits, it has also led to a dependency on the industry, altering the Sherpas' traditional subsistence activities such as agriculture and yak herding. The allure of better economic prospects has drawn younger Sherpas away from their ancestral professions towards tourism-related jobs, impacting the sustainability of traditional livelihoods.

Globalization has brought cultural exchanges between Sherpas and tourists, influencing the Sherpa way of life. Exposure to Western ideas, technology, and consumerism has influenced the younger generation's aspirations and values. There is an ongoing cultural assimilation and adaptation as Sherpas navigate between preserving their cultural heritage and embracing external influences.

Moreover, the influx of tourists and their expectations has prompted adaptations in Sherpa hospitality, traditions, and practices. While cultural exchanges can foster mutual understanding, there's a concern that these interactions might erode some aspects of Sherpa culture, especially among the younger generation more exposed to outside influences.

The environmental impact of globalization and increased tourism in the Himalayas has been a growing concern. The surge in visitors has led to issues like over-tourism in certain areas, putting a strain on local resources, trails, and accommodations. Improper waste management and pollution have become significant challenges, affecting the fragile ecosystem of the region.

Moreover, the changing climate, partly impaired by global factors, has impacted the Himalayan environment. Glacier retreat, unpredictable weather patterns, and an increase in natural disasters pose threats to the ecosystem and the Sherpa communities reliant on the mountains for their livelihoods.

Globalization has undoubtedly brought both positive and negative consequences for Sherpa communities and their ecosystems. While it has provided economic opportunities and cultural exchanges, it also poses challenges to traditional ways of life, cultural preservation, and environmental sustainability. Striking a balance between economic development, cultural preservation, and responsible tourism practices is crucial to ensure the well-being of Sherpa communities and the conservation of the pristine Himalayan environment for future generations. Collaborative efforts involving local communities, governments, and responsible tourism initiatives are essential to mitigate the negative impacts and foster sustainable development in the region.

Contrasting the educational paradigms of Nepal and the United States unraveled intriguing disparities and similarities. While Nepal’s educational system mirrors its cultural richness and communal values, the American system champions individualism and diversity. The emphasis on repetition learning in Nepal contrasts with the interactive and inquiry-based approach in the United States highlighted the vast spectrum of educational methodologies. However, both systems grapple with challenges such as access to quality education and socio-economic disparities, although in different contexts.

Exploring these interconnected themes has been an enlightening journey, broadening my perspective on the intricate work of global dynamics. The nuances of personal interactions, cultural exchanges, and environmental stewardship have underscored the imperative fostering empathy and understanding in a rapidly globalizing world. Furthermore, the comparative analysis of educational systems illuminated the importance of acknowledging diverse pedagogical approaches while striving for inclusivity and equity in education.

The comparison between a public school in the Himalayas and a public International Baccalaureate (IB) school in the United States reveals stark contrasts in educational systems, resources, methodologies, and cultural contexts. Here is a detailed examination of their differences: In Nepal there would be limited access to resources andinfrastructure due to remote locations and economic constraints. Classrooms may be basic with fewer amenities like technology, libraries, or laboratories. Schools may also have limited access to updated textbooks and educational materials. In addition, they often face challenges in providing quality education due to resource limitations.

Kokomo High School contains well-equipped classrooms with modern facilities, including technology, libraries, and laboratories. It also houses abundant access to updated textbooks, educational resources, and extracurricular activities. A greater availability of specialized teachers and staff for various subjects and student needs. While providing comprehensive support for students with diverse learning styles and needs.

Students in the Himalayan Public Schools may experience curriculum that might follow a national or regional educational framework, focusing on core subjects.Teaching methods may be more traditional, relying on memorization learning and teacher-centered approaches. While providing limited exposure to global perspectives or international curricula.

Whereas an IB curriculum at Kokomo High School may emphasize a broad and balanced education, encompassing various subjects and global perspectives. While teaching methods often encourage critical thinking, inquiry-based learning, and student-centered approaches. Kokomo High School also provides an emphasis on developing skills such as research, communication, and critical analysis.

In Nepal the culture is primarily a homogeneous student population predominantly reflecting local cultures and communities. There is limited exposure to cultural diversity due to geographic isolation. At Kokomo High School, a public IB School in the United States there is a diverse student body reflecting various ethnicities, cultures, and backgrounds. There are many more opportunities for cultural exchange and exposure to different perspectives due to a multicultural environment.

The educational philosophy and goals also vary from school to school. The Himalayan Public-School places an emphasis on imparting basic education and skills for practical life within the local context. The school also focuses on preserving local traditions, values, and societal needs. The Kokomo High School Public IB School in the United States places emphasis on holistic education, fostering international-mindedness, and developing global citizens. While engaging and placing high value and encouragement of critical thinking, creativity, and social responsibility.

The assessment and grading of a Himalayan Public School contains the assessment methods may be more traditional, relying on exams and standardized tests. The grading systems often are more rigid and focused on knowledge retention. At Kokomo High School there is an emphasis on various assessment methods, including presentations, projects, and research papers. The grading systems may incorporate holistic evaluation, considering skills and understanding, beyond just knowledge retention.

In conclusion, the comparison between a public school in the Himalayas and a public International Baccalaureate school in the United States underscores the significant disparities in educational resources, methodologies, cultural contexts, and goals. These differences reflect the diverse needs and challenges faced by educational institutions in various parts of the world, highlighting the importance of addressing educational disparities and promoting global educational equity.

In essence, the rich work of interconnected societies, cultures, and environments is a testament to our shared human experience. Understanding the implications of globalization on local communities and ecosystems while recognizing the educational diversity across nations provides a compass to navigate the complexities of our interconnected world. Embracing diversity, fostering sustainable interactions, and advocating for equitable education stand as pillars for nurturing a more inclusive and peaceful global society. This truly was one of the most amazing experiences of my life. Although, it’s over a new epic and incredible journey to see Everest awaits. In just a few weeks or so I will meet my son, Everest. Where one journey ends, another begins. Thank you for everything, John.

Victor Lorenz: Lesson 1

5 E LESSON: CONSEQUENCES OF CLIMATE CHANGE

IN THE HIMALAYAN MOUNTAINS

In my international baccalaureate, advanced placement, environmental science class we discuss the fundamental processes of climate change and relate it to specific locations where students can see the direct effects. I thought it was interesting to learn the effect climate change is having on the Himalayas. It was clear that both adults and children within the Sherpa community are concerned about climate change. They have witnessed the effects firsthand. I knew this would be a great lesson to discuss with students. I am anxious to present this lesson to students in second semester and hear their perspective on a nation that is witnessing climate change at an alarming rate.

My 5 E lesson from start to finish will take approximately one to two days to complete. Students will explore the multifaceted consequences of climate change in the Himalayan Mountains. They will investigate the environmental impact on surround ecosystems and the inevitable repercussions for the Khumbu communities. Through engaging activities and meaningful discussions, students will deepen their understanding of the complex issues related to climate change in the Himalayas.

Engagement may be the most critical step to any 5 E lesson. The engagement sets the foundation and really provides the “hook.” This step would take maybe ten minutes to complete. To begin, I would show a captivating image or video of the Himalayan Mountains. I would ask students to discuss their initial thoughts and observations about the image or video in small groups. This works out because my classroom is organized based on four students sitting at a lab table. I would facilitate a whole-class discussion, focusing on questions like: What do you notice about the landscape of the Himalayas? How do you think climate change might affect this region?

Exploration is giving students a chance to try out and use a variety of mediums to explore the “hook” on their own. Students will be provided with various sources that outline the environmental impacts of climate change in the Himalayan Mountains. The students will work at their tables in small groups to analyze a variety of different sources that discuss the key ideas. Students will be encouraged to identify the specific consequences on ecosystems and the local Khumbu region. Students will have about twenty minutes or so to explore through the sources.

At this point students have had the opportunity to explore different impacts of climate change. Students are now ready for an explanation and to build vocabulary. Building vocabulary is key and will take approximately twenty minutes. Teaching key terms should be much easier at this point in the unit, students will already understand and or be able to recognize many key concepts. Students will learn key terms such as: glacier advance, glacier retreat, avalanches, landslides, water scarcity, biodiversity loss, livelihood disruption. I could also bring in terms such as runoff, stream discharge, and velocity to further enhance the lesson. In environmental science it is not only beneficial to explain terms but to also display either images or video clips of new terminology to further understanding.

I would first explain the above terms through Canva or PowerPoint notes; students would find many illustrations, and examples of the key terms and concepts. I could also provide students with additional resources such as a short video clip or an additional sourced reading. I would allow students to reexamine materials used from the exploration stage to give students an opportunity to review the terms we discussed to check for understanding. Providing students additional time to connect and reflect would extend the time of this lesson but provide students a stronger knowledge foundation.

Students have now reached the elaboration stage. Students will spend approximately twenty minutes within the elaboration phase. In this stage students will elaborate on what they have learned. Students will be divided into pairs and assigned a specific consequence of climate change to research. Examples include melting glaciers, unpredictable weather conditions, quick moving cloud cover, changing rainfall patterns, and increased temperatures. Students will gather the information about the chosen climatic consequence, using well-cited sources. I will encourage critical thinking and a full analysis of the causes and potential solutions for each consequence.

I will ask students to think about what they have learned from our climate change topic. What questions can they think of that would pertain to understanding this concept even further? It needs to be a question where they can collect data. I would have them expand their current understanding of this concept by taking it a step further. My hope is that students will see the importance of climate change as it relates to not just the people and inhabitants of the Khumbu region of the Himalayan Mountains but also to the inhabitants on the other side of the world.

The last step to the 5 E Model is evaluation. At this point in the lesson students will reflect on each of the prior stages of the unit. I would give students the opportunity to think overnight about the consequences they and their partner researched. The following class period would begin the evaluation process. Students will recall the engagement, exploration, explanation, and elaboration stage of instructional development. To complete the evaluation portion of this lesson I would ask students in their pairs to present their findings to the class, focusing on consequences they researched. I would also guide a class discussion where students would make connections between their consequences presented and their wider implications. Each student would have the opportunity to contribute to the class discussion. Students would be assessed based on their active participation and contributions to the discussion.

To conclude the assignment, I would summarize the main consequences discussed during the lesson, emphasizing the multifaceted nature of climate change while asking students to reflect on the significance of understanding these consequences in the relationship between climate change. I could also assign a short survey or reflection paper to extend the evaluation process of this lesson.

Victor Lorenz: Lesson 2

5 E LESSON: ANALYZING PLATE TECTONIC FORCES IN THE FORMATION OF THE HIMALAYAN MOUNTAIN RANGE

In my international baccalaureate, advanced placement, environmental science class we discuss specific sites where we can see plate tectonic forces at play. There is no greater location to point to for continental-continental plate tectonic convergence than the Himalayan Mountains. I often refer to the Himalayas in my geology courses but find little time to discuss the Himalayan geology in environmental science. This lesson will be a great advertisement for both my physical and historical geology courses. I am excited to share this lesson with students. I certainly learned a lot about the geology of the Himalayan Mountains through my own research. I know I would not have set aside the time I did, had I not volunteered to give the presentation on Himalayan geology. John, thank you, I am always nervous presenting in front of my peers, but I did it. I learned far more than I would have, had I not volunteered to speak. Thanks for the confidence in me to present to others.

My 5 E lesson from start to finish will take approximately one and a half days to complete. The key question for my lesson is to have students analyze the plate tectonic forces between India and Asia to better understand geological processes that have shaped the Himalayan Mountain range, the highest elevated mountains in the world.

Engagement may be the most critical step to any 5 E lesson. The engagement sets the foundation and really provides the “hook.” This step would take maybe ten minutes to complete. To begin, I would show an image or video that I took at the top of Gokyo Ri. This image or video would clearly show the clear beauty of the Himalayan Mountain range. Students would then be provided with some Play-Doh. I would ask students to select two different colors of Play-Doh. The two different colored Play-Dohs will represent the two different tectonic plates. Students will remove the Play-Doh from the containers and roll out the Play-Doh making both colored sections of Play-Doh relatively flat. The two Play-Dohs will be separate from one another. The next step will involve students taking the two different Play-Dohs that are rolled out relatively flat and colliding them together. When students collide the Play-Dohs together they will see that the two Play-Dohs are relatively the same size density and mirror each other on both sides with multiple folds. I would ask students to share how mountains are formed and promote a brief class discussion to activate student’s prior knowledge and generate curiosity about mountain formation.

Exploration will provide students the opportunity to discover how mountains form. This step in the lesson will take approximately ten to twelve minutes to complete. Students will pull up Google Earth on their electronic devices. They will be asked to locate India and Asia. I will explain that the Himalayan Mountains range is found between these two landmasses. Students will then be divided into small groups and provided with resource links to gather information about the plate tectonic forces and geological processes that have shaped the Himalayas. I will encourage students to take notes, highlight, make a bulleted list, and or write down any questions they may have about plate tectonic forces or geologic processes.

At this point students have had the opportunity to explore different plate tectonic forces and geologic processes. Students are now ready to participate in the explanation process of what they learned with the rest of the class. At the front of my classroom, I will have labeled on one side of the white board plate tectonic forces and on the other side of the white board geologic processes. Students will group by group discuss what information they collected, and I will add it to the whiteboard. I will also add in and discuss any misconceptions or key information that looks missing. This is an opportunity to build vocabulary. Additional instructional tools like diagrams and videos will be available for students to review. Key terms include convergent boundary, subduction, plates, asthenosphere, thrust fault. I could also display small samples of rocks collected or comparable to the rocks found within the Himalayas. Students will spend approximately ten to fifteen minutes participating in this whole-class discussion based on the group’s findings from the explore phase.

Students will have the rest of the period to prepare for the elaboration phase. In this stage students will be divided back into their small groups. Each group will be provided with additional resources, such as scientific articles or online scientific journals to further explore their topic. Students should investigate into one aspect of the plate tectonic forces or geologic processes involved in the formation of the Himalayan Mountain range. Students will then analyze the cause-and-effect relationship and present their discoveries to the class in a digital formatted presentation.

The last step to the 5 E Model is evaluation. At this point in the lesson students will reflect on each of the prior stages of the unit and our key question. Students will write a short reflection paper based on what they have learned about the plate tectonic forces and geologic processes that have shaped the Himalayan Mountain range. Once I have each student response, I can fairly assess student understanding and guide students who might still have misconceptions or need additional resources.

To conclude the assignment, I would review key concepts and terminology that had been discussed throughout the lesson. I would place a strong significance on the plate tectonic forces and geologic processes responsible for the formation of the Himalayan Mountain range. I would encourage students to think about other mountain ranges and how they have formed. I would propose students to think about places they have visited, have there been any mountains? If so, did they form like the Himalayas or were they shaped by other plate tectonic forces or geologic processes?

Victor Lorenz: Lesson 3

5 E LESSON: ANALYZING THE IMPLICATIONS OF GLACIAL RUNOFF IN THE HIMALAYAN MOUNTAINS FOR HYDROELECTRIC PRODUCTION

In my international baccalaureate, advanced placement, environmental science class we discuss various types of nonrenewable and renewable resources. Students will look at costs and benefits of each resource. This year I thought it would be interesting to have students look at various communities that utilize specific renewable resources.

My 5 E lesson from start to finish will take approximately one day to complete. Students will be provided with a quiz through Google Forms on the second day. The key question for my lesson is to have students analyze the glacial runoff that is powering the Sherpa culture and tourists that trek through the Himalayan Mountain range.

Engagement may be the most critical step to any 5 E lesson. The engagement sets the foundation and really provides the “hook.” This step would take maybe five minutes or so to complete. To begin, I would show a beautiful image of the Himalayan Mountains with snow peaks and discuss their beauty. I would ask students to share what they know or have heard about the Himalayan Mountains and their environmental importance. I would then introduce the topic of glacial runoff and discuss the potential for hydroelectricity production, highlighting environmental and socioeconomic implications for the Sherpa community and tourism.

The exploration phase will provide students the opportunity to work in small groups for approximately ten minutes reading through information on Himalayan rivers and glaciers while viewing topographic maps. Students will be instructed to read through the articles and identify key information related to the environmental and socioeconomic implications of using glacial runoff for hydroelectricity production. I will encourage students to discuss and share their findings within their groups.

At this point students will have had the opportunity to explore the Himalayan terrane. Students will be familiar with glacial locations and stream valleys. Students are now ready to participate in the explanation process of what they learned with the rest of the class. Students will utilize a Google Jam Board to graphically organize and display their groups information. Once students record their group’s information in the Jam Board, I will discuss the Jam Board entries with the class. My primary focus will be to ensure students are familiar with key terms and concepts and redirect any misconceptions. This phase of the lesson is an opportunity to build a solid foundation in which students will be confident and ready to elaborate. When teaching new key terms it’s important to have different methods of instruction for different styles of learners. Whether it includes the additional resources or resources that support different reading levels or images and videos for those visual learners. Key terms include renewable energy, hydroelectricity, dams, glaciers, glacial runoff, environmental and socioeconomic implications. Students will spend approximately fifteen minutes participating in this lesson phase based on the group’s findings from the explore phase.

Students will have the rest of the period to prepare for the elaboration phase. In this stage students will have the opportunity to work individually or in pairs to brainstorm potential solutions or strategies to mitigate the negative environmental and socioeconomic impacts of glacial runoff for hydroelectricity production. I will encourage students to consider alternative energy sources or methods, and the potential trade-offs associated with each option. Each student or group will have the opportunity to present their ideas to the class. While students present, I will be taking notes and facilitating a discussion on the probability and effectiveness of the proposed student solutions.

The last step to the 5 E Model is evaluation. At this point in the lesson students will reflect on each of the prior stages of the unit and our key question. Students will complete a short true or false quiz through Google Forms. Once I have each student response, I can fairly evaluate student comprehension and guide students who might still have misconceptions or need additional resources to strengthen their understanding. An example question might include a true or false question that states, “The use of glacial runoff in the Himalayan Mountains for hydroelectricity production has no negative impact on the environment.”

To conclude the assignment, I would review key concepts and terminology that had been discussed throughout the lesson. I would place a strong significance on the connection between glaciers melting, rivers rising, and an increase in hydroelectricity production. I would encourage students to think about other locations in which glaciers are melting and if those locations could also utilize a hydroelectric power supply. I would encourage students to also think about what power generation means for societies that have little power supply or electricity needs that are currently being met.

Victor Lorenz: Lesson 4

5 E LESSON: ANALYZING THE SOCIO-CULTURAL CONSEQUENCES OF TOURISM IN THE HIMALAYAS ON THE SHERPA COMMUNITY

In my international baccalaureate, advanced placement, environmental science class we discuss the impact of population growth and how population impacts a region. I like to find new locations or cultures each year in which students can analyze population growth and reflect upon how it impacts that region. I find the sherpa culture to be fascinating and came up with this lesson as we were trekking back down from Namche Bazaar. Pemba’s evening talk at the Khumbu Lodge was instrumental in the innovation of this lesson. I knew this would be a great lesson to connect students with the sherpa culture. I am excited to present this lesson to see if students find sherpa culture as fascinating as I did while making a connection to sustainability, population, and economics.

My 5 E lesson from start to finish will take approximately one to two days to complete. The main objective is to analyze the socio-cultural consequences of the exponential rise in tourism in the Himalayas on the indigenous Sherpa community, including impacts on their traditional way of life, cultural values, and local economy, while considering potential strategies for sustainable tourism management.

Engagement may be the most critical step to any 5 E lesson. The engagement sets the foundation and really provides the “hook.” This step would take maybe ten minutes to complete. To begin, I would show images or videos that I took of the Sherpa community engaged in traditional ways of life. I would ask students to share any initial thoughts or observations they have concerning the Sherpas. The knowledge would be first based on the “hook” I provide. I would then ask if they had any outside knowledge or assumptions about the Sherpa community. If they did not have any previous knowledge about the Sherpa culture, I would pose the question: “How do you think the exponential rise in tourism might impact the traditional way of life and cultural values of the Sherpa community?”

Exploration is giving students a chance to try out and use a variety of mediums to explore the “hook” on their own. This segment will take approximately ten minutes to complete. Students will be divided into small groups and provided with printed or digital resources that discuss the consequences of tourism on the Sherpa community. These might be articles, videos like the one we saw at Sagarmatha Next or video interviews. In the student groups, students will analyze the resources and identify the impacts on the Sherpa community’s traditional way of life, cultural values, and local economy. I would encourage students to take foundational notes as they look through the resources on Sherpa culture. In small groups students will then share out their research with the class.

At this point students have had the opportunity to explore different impacts of tourism on Sherpa culture. Students are now ready for an explanation and to build vocabulary. Students will spend approximately twenty minutes participating in a whole-class discussion based on the group’s findings from the explore phase. While having a class discussion students will make connections between the impacts of tourism and the traditional way of life, cultural values, and local economy of the Sherpa community. Students will also learn the concept of sustainable tourism and its importance for balancing tourism growth with the preservation of cultural heritage.

Building vocabulary is also key during the explanation phase. Teaching key terms for this unit should be imbedded into our whole class discussion to make it easier for students to digest. Students should already be able to recognize many of the key terms and concepts. Students will have the opportunity to be introduced to key terms such as: the Sherpa community, socio-cultural consequences, exponential rises, traditional ways of life, cultural values, local economy, and sustainable tourism management. I could also bring in supporting terms from our population and terrestrial pollution unit to further enhance the lesson.

Students have now reached the elaboration stage. Students will spend approximately twenty to thirty minutes within the elaboration phase. Students will have the rest of the period for planning purposes to prepare for elaboration. In this stage students will be dividing into small groups. Each group will be assigned a specific stakeholder role. The stakeholder roles include a Sherpa community member, government official, tourism operator, and an environmental activist. In their roles, students will engage in a debate activity to discuss potential strategies for sustainable tourism management in the Himalayan Mountains. Students will utilize information gathered about their selected stakeholder position to provide a position and or agreement toward the other positions. Students should also be mindful of the socio-cultural consequences and the interest of the different stakeholders.

I will ask students to reflect on their major takeaways from this activity by completing a Google survey form. The survey will ask them to reflect on each stakeholder role. My hope is that students will see the importance of each stakeholder.

The last step to the 5 E Model is evaluation. At this point in the lesson students will reflect on each of the prior stages of the unit and our key question. Students will write a short reflection paper based on their understanding of the socio-cultural consequences of the exponential rise in tourism in the Himalayas on the indigenous Sherpa community, including the impacts on their traditional way of life, cultural values, and local economy, while considering potential strategies for sustainable tourism management. This will be great practice in application and like a question they may be asked to answer in a free-response style question on the advanced placement exam.

To conclude the assignment, I would review key concepts and terminology discussed throughout the lesson. I would place a strong significance on the socio-cultural consequences of tourism on the Sherpa community and potential strategies for sustainable tourism management. This lesson could also provide students with the opportunity to understand the importance behind preservation of cultural heritage and promoting responsible tourism practices not just in the Himalayas but everywhere.

Victor Lorenz

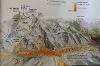

Embarking on a Geological Exploration: Nepal Evening Geology Talk

Brief History

-Mount Everest- Khumbu Region- Sagarmatha National Park (Himalayan Mountains)

- Elevation 29,031.69ft. (8,848.86 m) above sea level

-19th century- Great Trigonometrical Survey of India (The Mountains Western namesake is surveyor, General George Everest, a British geographer.)

-Sagarmatha- “Mother of the Universe”- Nepal

-Qomolangma (Chomolungma)- “Holy Mother” -Tibet

-As of July of 2022- 6,098 different people have stood on the summit.

-Tenzing Norgay – Edmund Hillary 1st to summit (8 attempts- 13 lives lost)

-Conrad Anker, legendary mountaineer stated, “The culmination of terrestrial exploration… at a time when humanity needed relief from 2 world wars. “A unifying and inspiring event, signifying the drive to reach our greatest potential.”

-The region known as Khumbu who is occupied by the people of eastern Himalaya- Sherpa or Sharwa

-1st Map produced by National Geographic 1933.

Geology Overview

-Karakoram-Himalayan-Tibetan Belt boasts a number of geologic superlatives:

-It contains the highest mountains on Earth (14 higher than 26,00 ft or over 8,000 m.)

-Greatest relief of any continent

-Highest uplift rates

-Largest concentration of glaciers outside of the polar regions,

-World’s highest and biggest plateau

-Source of many of the world’s greatest river systems

“Little wonder this region has attracted geologists since the early days of exploration and surveying.” -David R. Lageson

Historical Geology

-Where Tibet and Nepal meet

-Eurasia àß_India

-1,500 (2,494km) miles the Himalayas stretch from West to East.

-Our story begins 200 million years ago.

-Pangaea began to split- India broke free and headed toward Asia.

-India plate moved fast geologically speaking 30 ft. (9.1 m.) each century.

-Tethys Ocean was located between the gap of Eurasia and India.

-Oceanic plate pulled south edge of Eurasian Plate- subducted zone.

-Slow slip of oceanic slab into the mantle scrapped a thick layer of marine sediments into a pile on the south edge of Eurasian plate. This sandy layer with marine sediments would be squeezed into rock and end up on the mountain’s peaks of the Himalayas.

-Around 50 million years ago- India’s plates speed declined, a shift many scientists interpret as early stages of plate’s collision with Everest.

-Marine sediments suggest Tethys sea closed 50-60 mya.

-Unlike an ocean plate, which is cold and dense, India’s continental plate is thick and buoyant.

-So as continents compressed and India pushed it’s way under Asia, the surface buckled and the crust thickened to form the Himalayas.

-Scientists continue to ponder over every bend, crack, and rock in the system, many mysteries have arose.

-Study of ancient magnetic patterns in the rock allows researchers to chart a continents position over time, and recent work using this method has revealed that when the mountain forming collision took place some 55 million years ago, India would have been sitting far south from Eurasia. That would leave a mysterious yawning gap between the two continents.

-Did the India plate collide with a now long-gone landmass that sat between the 2 larger continental blocks?

-Could the Indian plate’s northern edge have extended much farther that previously thought?

-Why was the Indian plate moving so fast before impact?

-India creeps two inches (50mm) each year.

-Ongoing impact with Eurasia might force the mountain to ever greater heights, with an estimated average uplift of roughly 0.4 inch (10mm) a year in northwestern sections of the range, and around 0.04 (1mm) per/yr at Everest.

-Growth can happen in waves, brought on by more violet shifts in the landscape. As India collides beneath Eurasia it doesn’t always collide by smoothly.

-When compressed, pressure builds until hits a breaking point. The breaking point and sudden release of pressure provides the opportunity for earthquake movement.

-Mount Everest doesn’t necessarily get tall due to earthquakes. Most likely it deconstructs. It depends on where and how the ground moves.

-According to 2015 satellite data, the earthquake may have caused both growth and destruction of the mountain.

-Erosion can play a critical role from wind, water, ice, and gravity washing the sediments into the streams below into Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers.

-Sand drops out of the water as the slope diminishes at the mountains base in what is the largest river delta in the world, comparing the land that shifts under most of Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal.

-Even as erosion and gravity keep the mighty mountains in check, tectonic plates maintain their geologic dance-and Everest will continue to follow their lead. – Maya Wei-Haas

Bedrock Geology

4 Distinct Layers

-Summit

-Yellow Band

-Everest Series

-Hard Core

The Summit

Sedimentary- gray, laminated, silty limestone and dolomite

-Swiss geologist-Augusto Gansser, stated late Paleozoic in age ~300 mya

-More recently geologist have noted invert fossils and stratigraphic layers and studies in southern China that state as old as Ordovician age ~470 mya.

Yellow Band

-Most recognizable

-Yellow-tan marble “Gold Wedding Ring” – It circles the peak.

-Below Qomolangma (Chomolungma) detachment fault and crops out below the south summit on the Southeast Ridge and below the first step on the Northeast Ridge

-Its about 650 ft (198m) thick, it’s a succession of interbedded dolomite marble and phyllite a fine-grained metamorphic rock with a silky sheen.

-Middle Cambrian in age ~30-40 million years older than the Ordovician rock of the summit.

Everest Series

-Primarily low-grade metamorphic rocks mudstone/ shale and thin beds of marble.

-Minerals: albite (common feldspar, include pegmatites- coarser 1cm to m), chlorite, epidote (found in association with marble, schist, hydrothermal vents from dense mafic composition), biotite, and quartz.

-Deep water sediments deposited on the continental shelf north of supercontinent Gondwana.

-River system may have been the source for sand, silt, and clay. (Much like modern Mississippi River System dumps into Gulf.)

Hard Core

Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks

-Greater Himalayan Sequence

-Easily seen along Lukla to Everest Base Camp

-Dark Metamorphic Gneiss- Found in deep gorges cut by Dudh Kosi River

-Steep Switchback trail leading up to Namche Bazaar

-Notice Migmatite- a metamorphic rock that was once partially molten.

-Stone steps cut into the near vertical hill sides between Namche Bazaar, Phortze, and Tengboche provide fresh outcrops of metamorphic minerals.

-Ama Dablam and beyond to the lower Khumbu Glaciers you will see white granite in the boulders along the trail.

-At base camp, the landscape becomes monochromatic- a black and white vertical world of white granite and ice.

-This is the exhumed core, the inners of the Mountain Belt or upper crust of India that was detached, metamorphosed, thrown back on itself to the south to form greater Himalaya.

Ridges & Faces

Mountain Everest and Himalaya rose from the Tethys Ocean tens of millions of years ago as they rose they formed ridgelines and faces that have been shaped from not just plate tectonic movement but also glacial movement which we will learn about shortly.

Ridges of Everest

Northeast Ridge

-Marks the top of the North Ridge.

-Subdivides North Face

-Separates Everest from Changste (North Peak)

- 1 mile (1.6 km)

-Succession of overlapping sedimentary rocks (like shingles on a roof)

West Ridge

-3 miles (4.8km) from summit to Lho La, a col between Khumbutse and Everest.

Southeast Ridge

-1 mile (1.6km) long curves downward to the south col, which separates Everest and Lhotse,

-Creates blunt steep slopes of rock.

Faces of Everest

-North Face

-Southwest Face- Steep

-Kangshung Face= Icy

Surveying Mount Everest